Robert Perkins, Jr. is the founder of Wildlife Preserves, Inc. and served as its president for 66 years, from 1951 until his death in 2017.

Len Fariello served Wildlife Preserves, Inc. was hired as a ranger in 1973 and through the years he became Chief Ranger, Special Project Coordinator, Secretary, and eventually Land Manager for Wildlife Preserves and founder and manager of the Troy Meadows Wetland Mitigation Bank.

Mary Bruno published a book called An American River, all about the Passaic River. The book would not be complete without the story of Robert L. Perkins, Jr. and Wildlife Preserves, Inc. who helped preserve and protect much of the marshland within the Central Passaic Basin where Great Swamp, Black Meadows, Troy Meadows, Hatfield Swamp, and Great Piece Meadows are located.

In 2010, Mary Bruno interviewed Bob Perkins—and Len Fariello took her on a one-day tour through Troy and Great Piece Meadows.

The following excerpts are from her book—Chapter 6—Great Piece Meadows—page 149 begins the interview with Bob Perkins—and top of page 156 begins the tour with Len Fariello. It is reprinted below with permission:

An American River

Great Piece Meadows, Troy Meadows and Wildlife Preserves

by Mary Bruno

Bob Perkins Interview

The survival of wild life and wild places in New Jersey fills me with joy and amazement and a deep sense of gratitude. Sitting here in the warm spring hush of Great Piece Meadows, I marvel that someone, somewhere, somehow managed, against what must have been overwhelming odds, to wrestle this morsel of nature from the jaws of Garden State developers. It is a genuine miracle.

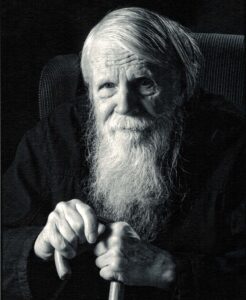

The miracle worker in the case of Great Piece Meadows is a man named Robert Perkins, the founder of Wildlife Preserves, Inc. And don’t get him started on conservation efforts in the Garden State. “You get into the politics of the last 100 years, which gets very turbid and is extremely unflattering to New Jersey,” says Perkins. “Think of a bunch of politicians sitting around belching over their last juicy steak. That’s a little unfair, but it’ll give you a sense. It’s a mess.”

Robert Perkins is a charming and elusive character. He is oddly cagey about his age, saying only that he was “alive in the 1930s,” and “in college in the 1950s,” which puts him somewhere just south of 80. We never meet in person. All our conversations take place by phone. Lucky for me, Perkins always answers his cell phone and despite his busy schedule he always seems to have time for a chat.

He was 11 years old when his parents moved from Greenwich, Connecticut to tiny Essex Fells, New Jersey, a 1.4-square mile village just east of the Hatfield Swamp. He lives in Tenafly now, a modest borough in northeastern Jersey whose 07670 zip code, notes Perkins, exhibits “complete bilateral symmetry.” Perkins was a born conservationist. “But I never should have gotten involved in New Jersey,” he says. “For a tiny, tiny part of the effort that we have put into New Jersey we could have accomplished vastly more in other places.”

That is no doubt true. But it is also true that without Perkins and his conservation efforts, the wetlands of the Passaic River’s Central Basin would have gone the way of the Newark Meadows. The tree-lined riverbanks that Carl and I have been paddling past today would likely shelter suburban cul-de-sacs rather than bobcats and bobolinks and the last of the blue-spotted salamanders.

Wildlife Preserves, Inc. (a.k.a. Wildlife), Robert Perkins’ Newark based organization, is a self-described “private, nonprofit conservation corporation dedicated to the preservation of natural areas and open space for conservation, education and research.” Perkins officially registered Wildlife Preserves in 1952, the year I was born. But his interest in preserving wildlife habitat began much earlier. At age nine, while he was strolling with an aunt through the Garden District of New Orleans, his father’s hometown, Perkins shared his sober and prescient concern that the human population boom was threatening to destroy the world. “I realized three things as a kid,” he says. “One was the rapidly growing population. Another was the growing power of small groups and individuals with technology. And the third was human nature. You put all three together and it’s disaster. At a very early age I was very pessimistic about the future. But I figured I still ought to do the best I could.”

Shortly after World War II, while he was a teenager attending boarding school in Vermont, Perkins convinced a handful of wealthy patrons to help him save some wildlife habitat. “They were fat cats,” says Perkins, about Wildlife’s original benefactors. “People that I knew about, or that some other friends had suggested.” Perkins’ father was a partner in one of Wall Street’s oldest and most prestigious law firms. The Perkins family wasn’t rich, but young Robert knew his way around the halls of power. “I was not very fat,” he says. “I wasn’t fat at all actually. But I got several people interested.”

By far the wealthiest patron Perkins courted was Mrs. Marcia Brady Tucker of Park Avenue in New York City. Marcia Tucker was the daughter of Anthony N. Brady, an Albany businessman who in partnership with Thomas Edison helped to found the Consolidated Edison and Union Carbide companies. When he died, Anthony Brady reportedly left one of the largest personal fortunes ever amassed. “Mrs. Tucker inherited a good deal of money,” says Perkins. Mrs. Tucker was also a lover of birds, and she had a keen interest in protecting them. Both privately and through her Marcia Tucker Brady Foundation, she became a principal patron of the American Ornithological Union. She sponsored exhibits at the American Museum of Natural History, entertained visiting ornithologists at her homes in Manhattan, Mount Kisco, New York and Florida, and served as a director for the National Audubon Society. In short, Mrs. Marcia Brady Tucker of Park Avenue in New York City was a prime candidate for a fundraising call.

“I remember the first time I met Mrs. Tucker,” says Perkins. “I was in my late teens. She had the only freestanding house on Park Avenue. I went there with a friend of hers. We walked in, and there was the butler, who greeted us, and three footmen. They each had these striped dickies and rows of brass buttons down the back of their tails. This was just for a casual visit in the afternoon. I’d been to a number of formal places before, but I was still amazed.”

Marcia Tucker died in December 1976 at the age of 93. The Park Avenue mansion that so dazzled the teenage Perkins has since been razed to make way for an apartment building. But through her generosity, Marcia Tucker’s spirit lives on in Great Piece Meadows.

Perkins and his investors decided to focus their acquisition efforts on wild areas within 200 miles of New York City. For guidance about which tracts were most worth preserving, they turned to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the federal agency that has been the steward of America’s national wildlife refuges since 1939.

Strange as it seems, there was no one date or event that compelled America to set aside habitat for wildlife, and no single person. The first federal effort to protect a natural area was the Congressional Act of June 30, 1864, which handed Yosemite Valley over to the State of California. Four years later, in 1868, President Ulysses S. Grant preserved the first federally-owned land when he took action to protect the fur seals on Alaska’s Pribiloff Islands. The preservation movement picked up considerable steam during Teddy Roosevelt’s turn-of-the-century administration. Roosevelt was a devoted hunter and outdoorsmen. His first conservation move was to declare Florida’s three-acre Pelican Island part of the public trust in 1903. Today’s Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge is considered the nation’s first true “refuge.” By the time Roosevelt left office in 1909, he had signed 51 Executive Orders that established wildlife preserves in l7 states and three U.S. territories.

The impetus for Roosevelt and for most federal set asides was a desire to protect the nation’s wildlife. During the last half of the 19th Century and into the early 20th Century, America’s birds and mammals were being hunted to extinction for their fur, feathers and eggs. Establishing sanctuary areas, where hunting was prohibited, seemed like a good start. But the original isolated pockets of nature weren’t large enough or contiguous enough to sustain migratory populations, which can travel thousands of miles. Besides which, preserving land by ad hoc executive fiats was not a sustainable public policy. If America really wanted to protect its wild lands and creatures, the country needed a bigger, better, more coordinated vision.

In 1918 and again in 1929, the federal government made several attempts to expand protections for migratory birds. But the National Wildlife Refuge System that we know today, with its familiar flying goose emblem, didn’t really begin to take shape until 1934, which turned out to be a watershed year for conservation.

Congress passed two pieces of landmark legislation that year. One was the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, which authorized the federal government to acquire wild lands that would be managed by the U.S. Biological Survey, a forerunner of the Fish & Wildlife Service. The other legislative action was the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act (a.k.a. the Duck Stamp Act), which authorized sales of a duck-hunting stamp to pay for the acquisition program. Also in 1934, the newly-elected president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, appointed a blue-ribbon panel to offer advice on how to protect America’s waterfowl. Members of the so-called “Duck Committee” were its chair Jay Norwood (“Ding”) Darling, Thomas Beck and Aldo Leopold. Never before or since has the cause of conservationism been championed by such eloquent emissaries with such a public platform.

“Ding” Darling was a Pulitzer prize-winning editorial cartoonist who promoted conservation with his syndicated drawings for the New York Herald Tribune. (After his Duck Committee days Darling went on to head the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey and found the National Wildlife Federation.) Thomas Beck chaired the Connecticut State Board of Fisheries and Game and was an editor for Collier’s Weekly, the groundbreaking investigative news magazine of the day. Aldo Leopold, the visionary ecologist and U.S. Forestry Service veteran, was a professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Like a modern Greek chorus, Darling, Beck and Leopold warned the public and the president about the growing dangers of habitat destruction and the pressing need for strategies and resources to combat it.

In the years following 1934, the government acted on many Duck Committee recommendations. The Bureau of Biological Survey began to steadily accumulate land around the country for the purpose of creating national wildlife sanctuaries. In 1939, its successor agency, the newly minted U.S. Fish & Wildlife Survey, purchased a labyrinth of salt marsh, coves and bays in Brigantine, New Jersey, a coastal community just 10 miles north of Atlantic City. The former Brigantine National Wildlife Refuge is now part of the larger Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, 46,000 acres of coastal wetlands and woodlands in New Jersey’s Atlantic, Burlington and Ocean counties. Today, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service manages 96 million acres of protected habitat in 548 refuges spread across all 50 states. But there was at least one refuge that got away.

Fish & Wildlife officials harbored ambitious plans to create a Passaic Valley National Wildlife Refuge in the 30-mile-long basin of ancient Glacial Lake Passaic. “They had made maps for acquisition, set a boundary and had all the various landowners listed,” says Robert Perkins. Then World War II broke out and acquisition efforts ground to a halt. When the war ended, attitudes about conservation and open space began to change “The GIs were coming home and having families,” says Perkins. “Big families.” With affordable G.I. Bill loans, those veterans were able to buy homes and start businesses. In New Jersey, the push to develop land began to overtake any interest in protecting it.

In 1956, the U.S. Congress passed the Fish and Wildlife Act. The legislation actually broadened the authority of federal agencies to purchase and develop land for new wildlife sanctuaries. But the bill didn’t provide money to underwrite the expansion. Without federal acquisition dollars, the public refuge movement sputtered and stalled. So when Perkins and his investment syndicate approached U.S. Fish & Wildlife officials for recommendations about which properties to purchase, the agency was thrilled, recalls Perkins. “They urged us to get both Troy and Piece meadows.”

Even with the benefit of private dollars and the support of U.S. Fish & Wildlife, acquiring the properties proved to be a long and arduous process. Both Great Piece Meadows and Troy Meadows were a checkerboard of tiny narrow lots. “The biggest piece was only about 50 acres and that was unusual,” says Perkins. “One plot was 100 feet wide and 9,000 feet long. We had the idea of putting a super bowling alley there.”

Wildlife Preserves, Inc. spent the 1950s and 1960s tracking down and negotiating with more than 100 different landowners. “Some of them had owned farms in the 1800s or 1700s and the farm would buy a little tract in the meadows as a source of timber and bedding hay, maybe only two or three acres,” says Perkins. “Except along the roads on the edge of the meadows, none of the owners lived there. Some owners had just disappeared.”

Despite the difficulties, Wildlife managed to round up an impressive share of the basin that once contained Glacial Lake Passaic, including 2,500 acres in Troy Meadows and 500 acres in Great Piece Meadows. (The organization currently owns about 6,000 acres throughout New Jersey.)

Wildlife was only able to grab fragments in Great Piece Meadows, a small tract here, a small tract there. But in the long run the fractured nature of the group’s holdings turned out to be a strategic advantage. “The town of Fairfield wanted Great Piece Meadows developed,” says Perkins. But every time town officials tried to build in Great Peace Meadows, some little wedge of Wildlife land got in the way of their plan. “By being scattered around,” says Perkins, “our property prevented any major development.” In Great Piece Meadows, that is.

Continuously thwarted in its efforts to build in Great Piece Meadows, the Township of Fairfield drained and developed Little Piece Meadows instead. That decision haunts local property owners, taxpayers and the Federal Emergency Management Agency every time a big storm swells the Passaic. The Willowbrook Mall in nearby Wayne, New Jersey was built on top of Little Piece Meadows. The 200-store retail temple is one of New Jersey’s oldest and largest shopping centers. In August 2011, torrential rains from Hurricane Irene left every store in the mall—and most of Fairfield Township—under four feet of water.

Wildlife Preserves, Inc. hasn’t been able to shield Great Piece Meadows and Troy Meadows from all the forces that threaten their ecology. The road salt that bordering towns heap onto local streets and highways in wintertime has begun to alter the freshwater character of the wetlands. In many places, the invasive reed Phragmites, which can tolerate salt, has replaced the once large stands of cattails (Typha), which cannot. Ditches dug to drain standing water and control mosquitoes are lowering the natural water table in the meadows, which may explain the decline in the populations of black ducks that feed and nest there.

As Wildlife’s Land Manager, Leonardo (“Len”) Fariello worries about these and other assaults on the meadows’ fragile ecosystem. “The biggest threat is human beings and human activity,” he says. “When I was growing up here more than half the land was vacant. It was just awesome. It all changed so fast. Who knew it was going to be covered over with all this suburbia?”

Len Fariello’s Interview and Tour

I drove out to Len Fariello’s house in Whippany on a drizzly July morning. He had agreed to take me on a tour of Troy Meadows and Great Piece Meadows. “We’re going to get wet,” he said, as he opened his front door.

Len is short and dark and handsome. His thick dark hair was slicked back. He wore cut-off blue jeans, a black t-shirt and a pair of beat up running shoes. He had a pinky ring on his left hand and a diamond-studded gold band on the ring finger of his right.

He led me back into his kitchen, which was crowded with rocks, fossils, Native American artifacts, antique telephones and dozens of vintage glass milk bottles displayed on a high wraparound shelf. Old pint milk bottles are a passion of Len’s. He fills them with white Styrofoam beads to make the logos from the long-gone local dairy farms pop. “I’m a collector,” he acknowledged: “of everything.” Including the three dogs yipping and scratching at the outside of the kitchen door— and the five orphaned raccoons, three baby skunks, ‘possums and grey squirrels that share a fenced enclosure in the backyard.

Len unfolded several large maps of Great Piece Meadows and spread them out carefully on the kitchen table. I could clearly see the property lanes that Robert Perkins had described. One map, a plat map of Great Piece Meadows prepared by the Army Corps of Engineers, showed the slim slats of land tucked together tongue-and-groove like floor planks. “In Fairfield Township, one half of Great Piece Meadows is designated a wildlife management area, the other is a wildlife sanctuary,” said Len, pointing out the two sectors on the map. Hunting is allowed in the wildlife management area, which is mostly owned by Fairfield. That’s where members of the Fairfield Conservation and Sportsman’s Association hunt. But hunting was and is illegal in the sanctuary areas owned by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and managed by Wildlife Preserves, Inc. Part of Len’s job is patrolling the boundaries where the two zones meet.

We set off in Len’s green Chevy truck, the maps and a portable GPS wedged between the dashboard and the windshield. We drove north for about ten minutes then turned east onto Troy Meadow Road, a rutted, grass-covered trail that runs straight through the middle of Troy Meadows. The Passaic was about seven miles to the east. The night before, severe thunderstorms dumped nearly two inches of rain on this part of northern New Jersey. There was standing water everywhere. When we reached the spot where West Brook joins Troy Brook, just a few yards to the north of Troy Meadow Road, the passage was flooded. We bumped and rolled and sloshed through swirling creek water, which in places covered the wheel wells. We were moving through a forest of young trees. The foot-high grasses that carpeted the road and the forest floor were neon green.

Len stopped the truck beside a red metal gate. The heavy gateposts were bent in opposite directions. The gate had come unhitched from the right post. That end rested a kilter on the ground. We stepped over it easily and walked a short distance through a grassy tunnel of trees that opened into a small clearing in the woods. “It was right here,” said Len, as he stood on a low mound at the edge of the clearing closest to the truck.

The mound was the site of the burned down shack that Len was squatting in when he got busted by wildlife rangers back in September 1973. The rangers knew Len. He was the local nature boy from Whippany, a regular Huck Finn. He and his childhood pals used to run a raft up and down the Whippany River. (The Whippany tracks the eastern edge of Troy Meadows on its way to meet the Passaic.) September is the start of New Jersey’s duck hunting season. The Wildlife rangers figured they could use an extra hand, so they offered Len a job keeping poachers off the wildlife preserves in Great Piece and Troy Meadows.

“I went by the name of Running Deer back then,” said Len, who in his younger days was preternaturally fleet. He was New Jersey’s high school Cross-Country Champ in 1965. “I was a bare-footer, except in the dead of winter. The bottoms of my feet were calloused like leather.” Running Deer was a lot faster and a lot quieter than his typical prey, the hunters in their clumsy rubber boots or hip waders. He bagged some 60 poachers in the Troy Meadows sanctuary that first season.

Len stayed on with Wildlife for the next three years. He fixed up the cabin, scrounging a wood stove, and installing a screen door and windows and a skylight where some vandal had blown a shotgun hole through the roof. “I slept in a loft under the moon and stars,” he told me. “It was pretty primitive, but that’s how my life was back then. I was just playing.” Len was serious about his work though. During his time as a ranger, Len vigorously enforced the hunting ban on Wildlife property, waging war against poachers and becoming something of a legend in the process.

He was uncanny in his ability to track poachers and relentless in his pursuit. It was common for him to go crashing through stands of cattails on the heels of fleeing deer and duck hunters armed with shotguns or long-bladed hunting knives and high-powered bows. Not surprisingly, Len endured his share of retaliation over the years. He’s been punched and showered with birdshot. He was knocked down and run over by one group of angry violators when he refused to back away from the grill of their jeep.

“I had a hunter draw his bow on me once,” Len recalled. The bow incident happened on a chill, damp autumn afternoon when Len and a partner were out patrolling the edge of the swamp. Len noticed some fresh boot tracks in the mud. “Most bow hunters hunt from trees,” he said. “I probably wouldn’t have seen this guy if he had just stayed still and hugged the trunk, but he panicked, scrambled down the tree and started running.”

Len took off after him. After a half mile run through deep water, Len caught up with the hunter at the edge of the woods behind some houses. Then all hell broke loose.

“He notches an arrow and draws back on me with a four-blade razor point aimed at my chest,” recalled Len. “He’s in full camo, including face paint. He’s yelling, ‘Stay back! Stay back!’ Dogs start barking. Girls start screaming. I’m yelling call the police! Call the police!”

In all the commotion, the bow hunter managed to duck into one of the nearby houses. Local police eventually negotiated a surrender. “Turns out it was a notorious trapper and poacher I’d tangled with before,” said Len. “I never recognized him that day with all his camo and hunting regalia.”

All in all, Wildlife Preserves, Inc. successfully prosecuted about a third of Len’s collars. “I sort of cleaned up the area,” he said. And then, in 1976, he left New Jersey.

Len wound up in Arkansas’ Ozark Mountains. He bought some land and took up farming, raising beef cattle and cultivating crops and medicinal roots and herbs. The locals knew him as “Len Sunchild” or “Doc.” Bob Perkins got in touch every September, to see if Running Deer would come back and help out during hunting season. Most years, Len would go. “I never broke my connection with Wildlife Preserves,” he said. It was a good thing too, because after a decade in the Ozarks, with no TV, radio, telephone, electricity or company, even Len was ready to “get back to society.”

In 1986, he returned to New Jersey and to fulltime work with Wildlife. He married a Whippany girl, had two kids. Running Deer domesticated. Len and his wife are divorced now. But he still lives in Whippany with his daughter and son, and he still works for Wildlife. Len has been the organization’s Land Manager for more than a decade.

Each fall, when he would arrive in New Jersey from Arkansas to work the hunting season for Wildlife, he’d be struck anew by the changes. “All the places I played in as a kid were being paved over and developed,” he said. The dramatic changes moved Len to write books about his youthful adventures (The Nature of Changing Times) and about his once rural hometown. A Place Called Whippany: The History and Contemporary Times of Hanover Township, New Jersey, was first published in 1998. Len dedicated the book to his daughter Lydia and son Luca and “To the children of the future and the spirit of the past.”

It seems that every New Jersey nature lover has some wrenching tale about a desecration of the natural world. A woodland bulldozed, a river dammed, a pasture paved. For the storyteller, the assault is often so brutal and so careless that it has the feel of terrorism. Len Fariello’s tale involved an old beech tree that grew behind his childhood home.

Len grew up on the edge of Whippany Farm, a 138-acre estate originally owned by the Frelinghuysens, a prominent Morris County family. His backyard was a lush undisturbed forest with towering stands of sycamore, oak, tulip and hickory trees and one magnificent grove of virgin beeches that occupied an oxbow of the Whippany River. One of the oldest and most graceful beeches stood right behind Len’s house.

“It had an enormous five-foot diameter trunk,” said Len. “Five kids with joined hands could barely encircle it. There were ‘possum and ‘coon dens in it, and song bird nests and a wood duck nest in the top, and my friend and I built a tree house in it, way up high where only we could climb.”

In 1972, when Len was a teenager, the state of New Jersey began work on an extension of Route 287. For the northernmost stretch of highway, the state appropriated portions of Whippany Farm and of the Fariello property. “When they built Route 287, they just cleared everything,” said Len. The backyard beech was among the thousands of trees felled in the process. “When they destroyed that forest,” he said, “I snapped.”

With the trees gone and his family displaced, Len eventually hopped on his Harley and spent the summer of ‘73 traveling the country to California and back. When the Harley broke down in Chicago on the way home, Len and his disabled bike hitched a ride back to New Jersey. With no money and no prospects, he took shelter in the loft of the old abandoned hunter’s shack in Troy Meadows, which is where the Wildlife rangers found him that September.

Len and I stepped gingerly around the old cabin site, careful to avoid the bricks and twisted cable and chunks of old rusted bed frame that poke up through the grass. We were looking for the footprint of the old fireplace. We found a female turkey instead. She was sitting on her nest, little more than a shallow depression in the tall grass. We stopped as soon as we spotted her, but she startled and flushed anyway, leaving her eight eggs behind. They were pale beige with brown speckles and surprisingly small, no bigger than large chicken eggs. When I chided the mother turkey for abandoning them, Len sided with the bird. “She probably made the right move,” he said. “She’ll be back.”

Before we left the old cabin site I snapped a picture of Len standing on the mound near what used to be his old front door. Knee-deep in the wet grass, with the forest at his back, Len stood up straight with his hands at his sides and looked directly into the camera. His strange half smile betrayed a trace of awkwardness at having his picture taken, and a hint of mischief, nostalgia, defiance and something else. It’s hard to say exactly. It was just Lenny, a John Muir/Joe Pesci mashup. The Jersey tough guy who can get all misty-eyed about bog turtles.

“At first, I ran away from the development,” said Len, as we walked back to the truck. But eventually, “I decided to take a stand and fight it.” When he returned from the Ozarks in 1986, Len formed a nonprofit group called Citizens for Controlled Development. He began publishing a newsletter that profiled natural areas threatened by development and offered practical tips on how to contain and manage growth. It wasn’t enough. “I was always arguing my case to the people who were in control,” he said. “I realized I had to be on the other side of the podium.” He decided to run for public office.

It took a few tries but in 1999, campaigning on a “Save It, Don’t Pave It” platform, candidate Len Fariello won his first political race— for councilman in Hanover Township. He served on the council for 10 years before retiring from politics in 2010. During his tenure, Len helped Hanover acquire more than 300 acres of open space, and sponsored several ordinances to protect natural areas and native trees.

In his dual careers as Wildlife Land Manager and local pol, Len came to appreciate the art of compromise. He’s been trying (unsuccessfully) to convince his boss, Robert Perkins, to develop parcels of Wildlife land for recreational use as a way to pay the bills. But Len is a pragmatist by necessity. At heart, he still fights for every stream, every tree, every turtle, bird and bug, and he mourns the loss of every spec of nature. Which is what makes the land and wildlife of Troy Meadows and Great Piece Meadows all the more precious to him.

On the drive from Troy Meadows to Great Piece that afternoon, Len spotted a dead mink on the side of Route 80. He pulled over to retrieve the body, stiff but intact. “We’ll find a better resting place for him,” said Len, tossing the mink into the bed of his truck. “When I take Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts into Great Piece Meadows or Troy Meadows, I tell them that this is the land for animals, not people. We’re entering their domain. People just don’t care about wildlife. The county, the state, they just want to take our land. They have no plan in place to protect and manage it. The Army Corps wants it for flood storage. The towns want it for recreation. They seem to be more concerned with human use, with grass and picnic benches. Their attitude is that it has to be improved.”

In 2006, Wildlife Preserves, Inc. sold 400 acres of its Great Piece property to the Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps, acting on behalf of the State of New Jersey, has been buying up Passaic River floodplain property as part of the so-called Passaic River Natural Flood Storage Area Project, a flood control program that was ratified by state legislators in 1999. Under the terms of the Great Piece sale, Wildlife continues to manage the property in partnership with the New Jersey Natural Lands Trust, a division of the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. But the Great Piece Meadows land is now subject to a “flood control easement,” explains Len, which means that the Army Corps can do pretty much whatever it wants in the name of flood control. “If you read the easement, it’ll scare the hell out of you. They’re buying the land for flood storage, but there’s all kinds of language where they can do a lot to manage floodwaters, [including] build dams and dikes, change the hydrology, control the water.”

Great Piece Meadows, as it exists today, may be one big flood away from an Army Corps makeover. Erecting dams or digging ditches may help to mitigate flooding in the Passaic’s River Valley. But such interventions are certain to disrupt the delicate balance of these Central Basin wetlands.